- Wilderness in Britain

E. M. Forster in 1964 wrote that two world wars had enveloped the wildness of Britain. “‘Two great wars demanded and bequeathed regimentation,’ wrote E. M. Forster in 1964, ‘science lent her aid, and the wildness of these islands, never extensive, was stamped upon and built over and patrolled in no time. There is no forest or fell to escape to today, no cave in which to curl up, and no deserted valley.’” (Macfarlane 2009, p.8)

Jonathan Raban claims Britain lost its wilderness much earlier in the 1860s with population and industry:

so thickly peopled, so intensively farmed, so industrialised, so citified, that there was nowhere to go to be truly alone, or to have … adventures, except to sea. (Jonathan Raban Cited in (Macfarlane 2009, p.8))

Macfarlane states population and the road network is really to blame for the lack of wilderness or remoteness:

In Britain, over sixty-one million people now live in 93,000 square miles of land. Remoteness has been almost abolished, and the main agents of that abolition have been the car and the road. Only a small and diminishing proportion of terrain is now more than five miles from a motorable surface. There are nearly thirty million cars in use in Britain, and 210,000 miles of road on the mainland alone. (Macfarlane 2009, p.9)

George Monbiot argues that there is a wildness paradox, that Britain's gardens have more wildlife in them than barren uplands:

Spend two hours sitting in a bushy suburban garden anywhere in Britain, and you are likely to see more birds, and of a wider range of species, than you would while walking five miles across almost any open landscape in the uplands. (Monbiot 2014, p.69)

Liz Wells argues Britain is a managed land and notes the paradox of the pictorial countryside as safe, clean, and undisturbed rather than managed.

...British land is managed – there is no wilderness; even the coastal littoral is overseen (by the Environment Agency). It follows that landscapes and vistas are human constructs, which means that aesthetic principles, as well as social mores, were and are in play within the actual shaping of land. Pictorial renderings of countryside as pastoral depict Britain as undisturbed and undisturbing, thus contributing to constructing a simplified and benign rural imaginary, to picturing countryside as safe. (Wells 2011, p.164)

The lack of wild animals like wolves, beaver and boar:

So few wild creatures, relatively, remain in Britain and Ireland: so few, relatively, in the world. Pursuing our project of civilisation, we have pushed thousands of species towards the brink of disappearance, and many thousands more over that edge. The loss, after it is theirs, is ours. Wild animals, like wild places, are invaluable to us precisely because they are not us. They are uncompromisingly different. (Macfarlane 2009, p.306,307)

References

Macfarlane, R., 2009. The Wild Places, Granta Books.

Monbiot, G., 2014. Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, University of Chicago Press.

Wells, L., 2011. Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity, I.B.Tauris.

- Rural facts

Woodland findings:

- The area of woodland in the UK at 31 March 2019 is estimated to be 3.19 million hectares. This represents 13% of the total land area in the UK, 10% in England, 15% in Wales, 19% in Scotland and 8% in Northern Ireland.

- Of the total UK woodland area, 0.86 million hectares (27%) is owned or managed by Forestry England, Forestry and Land Scotland, Natural Resources Wales or the Forest Service (in Northern Ireland).

- The total certified woodland area in the UK at 31 March 2019 is 1.40 million hectares, including all Forestry England/Forestry and Land Scotland1/Natural Resources Wales/Forest Service woodland. Overall, 44% of the UK woodland area is certified.

- Thirteen thousand hectares of new woodland were created in the UK in 2018-19, with conifers accounting for 60% of this area.

- A total of 842 sites were served with a Statutory Plant Health Notice in 2018-19, requiring a total of 3.8 thousand hectares of woodland to be felled. (This excludes areas felled within the Phytophthora ramorum management zone in south west Scotland, where a Statutory Plant Health Notice is not required).

- (Forestry Commission, 2019)

Rural affairs:

- In 2017/18 there were 545,000 businesses registered in rural areas, accounting for 24 per cent of all registered businesses in England.

- Businesses registered in rural areas employed 3.6 million people, accounting for 13 per cent of all those employed by registered businesses in England.

- There are more registered businesses per head of population in predominantly rural areas than in predominantly urban areas (excluding London).

- There are proportionately more small businesses in rural areas.

- In 2017 there were 46 registered business start-ups per 10,000 population in predominantly rural areas compared with 55 per 10,000 population in predominantly urban areas (excluding London).

- (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, 2019a)

Further rural affairs:

These figures are current until they are replaced on the 19th of December 2019.

Second estimate figures for 2018 compared to 2017, in current prices, show:

- Total Income from Farming fell by £971 million (17%) to £4,644 million

- Agriculture contributed £9,548 million or 0.51% to the national economy (Gross Value Added), a decrease of £651 million (6%) on the year.

The main drivers of these changes are:

An increase of £538 million (2%) in gross output to £26,562 million

An increase of £1,189 million (8%) in the value of intermediate consumption to £17,014 million

- Crop output value rose by 0.9% to £9,265 million. The cold, wet spring followed by the dry, hot summer contributed to lower yields of key crops however better prices helped offset production falls.

- The value of total livestock output rose by 2% to £14,741 million. Prices were generally higher but the challenging weather conditions affected volumes; the late cold spring disrupted lambing and the hot, dry summer led to poor grass growth and difficulties feeding livestock.

- In general all intermediate consumption costs rose, with fuel, feed and fertiliser costs showing the largest increases.

- (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, 2019b)

Bibliography

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2019a) ‘Rural businesses’. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/828079/Businesses_-_August_2019__includes_SME_update_.pdf (Accessed: 22 November 2019).

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2019b) ‘Total Income from Farming in the United Kingdom First estimate for 2018’. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/815301/agricaccounts-tiffstatsnotice-09jul19.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2019).

Forestry Commission (2019) ‘Forestry Statistics 2019’. Available at: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/documents/7435/Complete_FS2019_zIuGIog.pdf (Accessed: 8 December 2019).

- The Man made Peak

… the conservation movement, while well intentioned, has sought to freeze living systems in time. It attempts to prevent animals and plants from either leaving or–if they do not live there already–entering. It seeks to manage nature as if tending a garden. Many of the ecosystems, such as heath and moorland, blanket bog and rough grass, that it tries to preserve are dominated by the low, scrubby vegetation which remains after forests have been repeatedly cleared and burnt. This vegetation is cherished by wildlife groups, which prevent it from reverting to woodland through intensive grazing by sheep, cattle and horses. It is as if conservationists in the Amazon had decided to protect the cattle ranches, rather than the rainforest. (Monbiot, 2014, p. 8)

Management of moorland through cutting.

Out of 218 nations, the UK ranks 189th for the intactness of its living systems (rspb, 2016)

… In Britain, as in most of Western Europe, land is managed; it follows that vistas or landscapes are constructed, which means that a sense of aesthetic principles, as well as social mores, are in play. (Wells, 2011, p. 28)

Bibliography

Monbiot, G. (2014) Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life. University of Chicago Press.

rspb (2016) State of Nature 2016, https://www.rspb.org.uk/. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/conservation-projects/state-of-nature/state-of-nature-uk-report-2016.pdf (Accessed: 15 November 2019).

Wells, L. (2011) Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. I.B.Tauris.

- Notes on edgelands and crime

Through the lack of context and their subversive edgy characteristics, edgeland sites can harbour suspicion. These are out of town areas where the socially marginal meet for questionable or immoral activities. These dystopias are enforced and exploited through film and tv. Throughout the 1990's the backdrop of the indie crime movie was an edgeland site. The place where money is exchanged, money is stolen, and the criminal-protagonist cover is walking the dog. Of course, the edginess is hyperbole, visually enhanced with banal industrial architecture, debris and monotonous colour balances. Film portrays them as landscapes where concluding conflict is played out. In reality, these areas, besides the occasional glimpses of marginal society (the attempted dog theft) spurring suspicion, are not straightforward dystopias but banal urban peripheries with complex social processes.

Author of the term:

The aura of excitement which goes with the apparent lawlessness of the edgelands has been exploited in such films of the 1990s as Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Seven, Things to Do in Denver When you’re Dead, Fargo and The Straight Story. (Shoard, 2000, p. 130)

[[Roberts, M. S.]] co-author of edgelands Journeys Into England's True Wilderness (2011):

Marion Shoard’s coining of ‘edgelands’ seemed to conjure exactly our experience of these places. They were, and are, edgy. In British tv drama and low budget films, the edgelands are always the place of the dénouement, the place where the drug gang is busted, the car chase ends, or the kidnap victim is rescued. These are places where anything could happen. And when it did, it was usually illegal or contravened every rule of health and safety. This sense of the edgelands as a dystopian landscape is a familiar trope of British popular culture in particular. (Roberts, 2016, pp. 19–20)

Bibliography for this note

Roberts, M. S. (2016) ‘The Making of Edgelands’, English Topographies in Literature and Culture, pp. 17–24.

Shoard, M. (2000) ‘Edgelands of Promise’, Landscapes, pp. 117–146.

- Third landscape

( Tiers-Paysage )

A term for les délaissés (leftover spaces of urban development) for nature to colonise. Coined by Gilles Clément, a French garden designer, botanist, entomologist and writer, in a manifesto entitled ‘Manifeste du Tiers paysage’.

In ‘Manifeste du Tiers paysage’, Clément argues that neglected and unexploited space is a reserve under the term third landscape. Left to evolution, biological processes and agency transform anthropized territories to natural spaces which provide biodiverse habitats for fauna and flora but can also be used by society as spaces for leisure and connection to the natural world.

- Clément's Derborence Island, an inaccessible urban "garden" left to nature.

- Manifesto from Clément's website

- Edgelands

Coined by Marion Shoard (see Edgelands of Promise) and further popularised by Farley, P. and Symmons Roberts (See Edgelands Journeys Into Englands True Wilderness), the term can be confusing.

The term can refer to:

the indeterminate urban boundary between rural territories which can host infrastructure, golf courses, car parks and canals.

marginal areas outside of conventional urban circuits like derelict and brownfield sites.

non-places such as retail parks, service stations and transport infrastructure on the outskirts

- Terrain vague

French landscape theoretical term for indeterminate space, defined by Spanish architect, Ignasi de Solà- Morales, stating:

It is impossible to capture in a single English word or phrase the meaning of terrain vague. The French term terrain connotes a more urban quality than the English land; thus terrain is an extension of the precisely limited ground fit for construction, for the city.” (de Solà- Morales, 2013, p. 26).

Breaking down the etymology

- The term has duality stemming from Latin: “Vague descends from vacuus, giving us “vacant” and “vacuum” in English, which is to say “empty, unoccupied,” yet also “free, available, unengaged.”

- A second meaning superimposed on the French vague derives from the Latin vagus, giving “vague” in English, too, in the sense of “indeterminate, imprecise, blurred, uncertain.” (de Solà- Morales, 2013, p. 26).

- Solà- Morales uses the french term ‘terrain vague’ because the English vocabulary for these pockets of vacant landscape have negative connotations such as wasteland.

My favourite explanation

Stanka Radović has a clear definition in the essay ‘on the threshold’ - an essay using the Andrei Tarkovsky 1979 film, Stalker, to explore the term as a utopia:

“... terrain vague escapes and challenges rigid definitions. Is it urban or is it natural? Is it a concept or a concrete place? Free or forlorn? The term “terrain vague” translates into English as “wasteland,” “derelict area,” or “vacant land,” and refers to abandoned or unoccupied portions of urban land that remain available for spontaneous use.” (Radović, 2013, p. 114)

Early photography

Man Ray Etude pour terrain vague , 1929

Before de Solà- Morales, Man Ray, inspired by Eugène Atget, captioned these photographs 'Terrain Vague'.

Bibliography

Radović, S. (2013) ‘On the Threshold: Terrain Vague as Living Space in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker’, Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale.

de Solà- Morales, I. (2013) ‘Terrain Vague’, Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale.

- Non-place

Contemporary urban-culture areas of transit and commerce with a lack of history and “heightened sense of anonymity” (Barron, 2013, p. 6)

Bibliography

Barron, P. (2013) ‘Introduction: At the Edge of the Pale’. Routledge, pp. 1–23.

- Marginal space

Empty, unoccupied or peripheral urban spaces.

Terminology

Naming turns space into place (Wells, 2011, p. 3).

- Edgelands - indeterminate interfacial between urban and rural.

- Urban Wildscape - urban spaces under the agency of nature.

- Third landscape - spaces left to natural evolution.

- Non-place - contemporary urban spaces without history.

- Terrain vague - imprecise spaces.

Avoiding the predetermined

As a " " landscape photographer " " I constantly need reminding, that despite the above definitions, landscape is a “highly differentiated discourse on representing space” (Bate, 2009, p. 93).

Following a unique interpretation of a site whether that is through geography, autobiography, or metaphor, will create original work and avoid cliche.

Bibliography

Bate, D. (2009) Photography: The Key Concepts. Berg.

Wells, L. (2011) Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hokkaido highway blues

Burakumin:

The Japanese never talk about burakumin; they are the ghosts of the society. If you ask a colleague about this lower caste, he will either brush it off, or frown thoughtfully and try to change the subject. Those in even deeper stages of denial will insist that there is no such thing as burakumin. [...] (Burakumin towns traditionally did not exist; they were not marked on maps nor were they signposted, a habit that lingers in present municipal attitudes.) Page 173.

Western society is no better:

East Indians in England. Arabs in France. Aborigines in Australia. Natives in Canada and the United States. We have our own castes of outsiders. It is a human urge, this need to create outcasts; you will see it on Indian reservations and South African homelands. And in the burakumin villages of Japan. Page 173

Ōishi Yoshio and the 47 Ronin story page 213.

Genki. Genki-yo! Page 238

Yamabushi. page 312

Pizza toast. Page 328

Konnyaku - "devil's tongue". Bar toilet Graffiti: what is konnyaku? Where does it come from and what does it want? page 341

Hirosaki is the singularly most Japanese city I know. Not the finest or the prettiest or the oldest, but definitely the most Japanese. Page 345

Super Gaijin! TV show page 347

I had spent more than a month surrounded by them, more than is possible, more than is natural. And it struck me then, with a deep sense of unease, that what I was doing was fundamentally wrong. The sakura are meant to be transitory, ephemeral. To try to cling to them was like trying to cling to youth. Following the Cherry Blossom Front was a denial of time, of seasons, of mortality even. It was like spraying lacquer on a lily. Like embalming a mirage. Like trying to stop time. Page 353

- The Art of Flaneuring (2019)

by Erika Owen.

A short lifestyle guide to a subject associated with historic Parisian men in top hats or the contemporary psychogeographer stereotype of a white male with walking boots, shorts and hiking bag prowling urban spaces. The author sidesteps esotericism and repackages the flaneur pursuit as a laid back hygge-equivalent lifestyle to aid wellbeing.

Flaneurism as a lifestyle is not an outlandish proposal. Think back to when Instagram was fun and engaging. I know it was a long time ago, but content synonymous with the Flâneur like food, drink and travel was popular. The app at one time seemed like a plug for a spontaneous-engaging lifestyle. A more relevant simile is the conventional and contemporary domestic tourist navigating the city by foot from tourist attraction to hospitality.

Notes on The Art of Flaneuring:

Art:

Agnès Varda flaneur-like filmmaking

Beginner tips:

- Have good shoes.

- Break.

- Be playful -fight boredom.

- Journal

- Research new spaces

Creative:

- Put a line or circle through a map. Follow it.

- Trade walking journals.

Feminist interpretation:

- The 19th-century flaneur: "drunken, syphilitic men wandering around and allowing themselves to find romanticism or excitement or perversity."

- Lack of acknowledged historic and contemporary female flaneurs.

- Walking is freedom. No delays, no traffic, more personal space. Bypass designated travel methods and zones for your own route.

- Book: Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London by Lauren Elkin

- Elkin: ...tune in to your surroundings, no matter what they are, urban or not. And no matter who you are, just look around you and ask, "How is this world put together?" "How is it made easier for some people to navigate than others?" "What is my responsibility in this place where I spend every day, how am I a part of it, and how do I affect other people's experiences of it?"

Health:

Outside of France :

- Italy: passeggiata -an after-dinner stroll.

- Australia: the walkabout.

- Germany: geocaching remains popular.

- The UK

- Roamers (?) are a British equivalent, wandering and appreciating tiny details. Does the author mean Ramblers? Perhaps urban or radical ramblers.

- Ramblers don't lose your way campaign to save paths

Race:

- Soul of place (2015)

by Linda Lappin.

A creative landscape-writing workbook. Though aimed at literature/creative writing, it can be used as a source of inspiration for different mediums such as landscape-psychogeography photography projects.

- Deep map

- Postcard fiction

- Word painting -visual descriptions of a place

- Pilgrimage

- Follow off the beaten track

- Visit a place no longer there

- A literary journey

- A quest: a journey in parts (1) a desire, (2) a conflict, and (3) breakthrough

- Finding the soul of the city

- How do seasonal changes affect the place - holidays, weather

- History

- Who lived there?

- Your personal mythology-geography

- Parks

- Wild / cultivated dichotomy

- How the natural elements work together

- Pathways, design and purpose

- Animals and people

- Art - statues, design

- Transportation links

- Types of commuter

- Modes

- Types of personal transport

- Drivers

- Ruins

Landscape And Memory - Simon Schama (1996)

Landscape And Memory - Simon Schama (1996)Landscapes are culture before they are nature; constructs of the imagination projected onto wood and water and rock. So goes the argument of this book. But it should also be acknowledged that once a certain idea of landscape, a myth, a vision, establishes itself in an actual place, it has a peculiar way of muddling categories, of making metaphors more real than their referents; of becoming, in fact, part of the scenery.

page 61

Ginn, F. (2017) Domestic Wild. Memory, Nature and Gardening in Suburbia

Ginn, F. (2017) Domestic Wild. Memory, Nature and Gardening in SuburbiaRegarding nature and culture dichotomy

Instead of a nature–culture dualism that has been eroded by historical events, a broad movement across the social sciences and social theory has advanced the claim that the world has always been comprised of entanglements between humans, creatures and agents of all kinds. This movement has been inspired by the philosophies of, among others, Bruno Latour, Donna Haraway and Gilles Deleuze and their antipathy to ontological hygiene. (Ginn, 2017, p. 5)

Ginn points to philosophers such as Bruno Latour, who’s 1991 work, Nous n'avons jamais été modernes, argues the dichotomy never existed.

… nature and culture are conceptual abstractions and so our present era – although it is an era of great loss – is not a loss of the wild brought about by the enclosure of nature within culture. Rather, the twenty-first century has witnessed a step-change in the intensity of planetary circulation and metabolism (Ginn, 2017, p. 5).

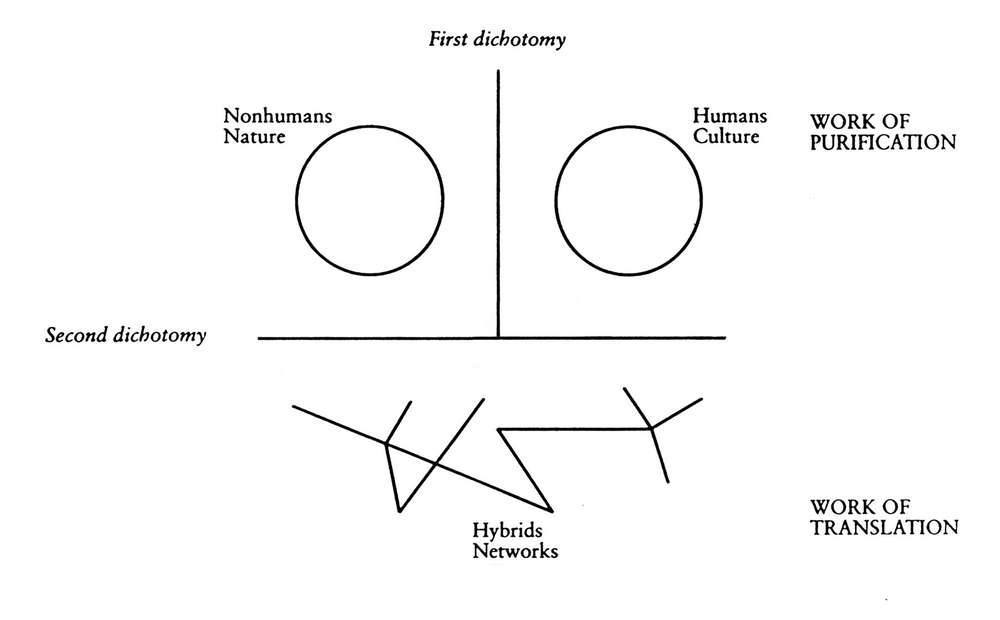

Ginn states that culture has not consumed nature (extinctions), but connected with nature through an increasing number of interconnections at a global level. This reminds me of fig.1.1 in Latours translated, We have never been modern? (Latour, 1993, p. 11) in which nonhuman nature and human culture are depicted along a second dichotomy separating the nature-culture dualism with that of a hybridised network of connections.

Gardening shrugs in the face of the nature–culture dualism. Gardening has never really been something done by humans to plants, but has always been a process of mutually beneficial interkingdom exchange. (Ginn, 2017, p. 6).

In relation to gardening, the interconnections between nature-culture are apparent and beneficial for both.

The Anthropocene seems to unite humanity. But it does so through ‘our’ unequally shared vulnerability to forces of capitalist world ecology and global environmental change. Instead of being united by negative unity – that of vulnerability and loss – might we not seek a more compassionate and affirmative acknowledgement of unity? Gardening, as the domestic wild, might allow us a way to imagine an earthly ethos fit for the Anthropocene. (Ginn, 2017, p. 142)

Ginn’s concluding message is that gardening may provide a force for good in the anthropocene landscape as a positive interconnection between nonhuman and human culture.

Bibliography

Ginn, F. (2017) Domestic Wild: Memory, Nature and Gardening in Suburbia. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Latour, B. (1993) We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.

- Losing Eden (2020)

Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones

Contemporary literary work on the British landscape tends to be a focus on nature, wilderness, or wonder. This, however, focuses on the wellbeing and health benefits of nature. Backed by scientific research, it features a substantial scientific and academic bibliography in conjunction with accessible writing.

Introduction chapter

Terms

Psychoterratic - mental health in relation to the earth.

Psychoterratic illnesses, for example, are earth-related mental health issues such as ecoanxiety and global dread.

Solastalgia - is when your endemic sense of place is being violated.

‘Solastalgia’ – an admixture of solace, nostalgia and destruction – describes a feeling of nostalgia and powerlessness about a place that once brought solace which has been destroyed.

Species loneliness:

...to mean a collective sorrow and anxiety arising from our disconnection from other species.

I enjoyed and agreed with this:

...it would appear that industrialized society perceives nature to be little more than a nicety: a luxury, an extra, a garnish – ‘Green crap’, as the former prime minister David Cameron reportedly called environmental policies

Brief timeline of cultures relationship with nature

Arcadia:

Virgil’s account of Arcadia, from his Eclogues (also known as the Bucolics), was a landscape of comfort and healing – with its cool springs, zephyrs, laurels and tamarisks – for Gallus, who was dying of a broken heart.

Industrialization:

...as the West became industrialized and our contact and connection with the natural world around us dwindled. As people moved to cities, and away from the land, they had to actively seek out nature, as they became physically separated from it. In the pre-industrialized West, the wilderness was often seen as cruel, revolting and ugly

Romanization of nature:

from the eighteenth century onwards people began to see the natural landscape in a new way, and with the rise of the Romantic movement in art and poetry, and Transcendentalists such as Henry Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson

After a brief timeline, Jones discusses post-industrial attitudes to nature and mental health with Victorian/Edwardian asylums having gardens. Followed by contemporary nature therapy and the authors personal interest.

Chapter 1

Mycobacterium vaccae:

hypothesize that an immune response to M. vaccae stimulates the brain to create more serotonin, the happy chemical that antidepressant pills are designed to boost.