An essay about Fay Godwin and the British landscape, written during my degree in 2017.

The notion of ‘Landscape’ in Britain implores images of coastlines, rivers, canals, fields, moorland, hills, mountains, villages and gardens. Though broad in scope, these designations and types of environment are far away from the notion of ‘wilderness’. Like the extinct wolves and lynxes which were indigenous to the British isles so to has the swathes of untouched forest and moorland become extinct, carved up, transformed and managed. The entire land and sea is managed, creating a link between the British landscape and the idea of land ownership. The British ‘countryside’ is a social construct of history, privilege, and ownership with hedges, fences and stonewalls carving up the land, whilst castles to village cottages lay claim to land. Pictorial British landscapes only enforce this idea of ownership, as Berger suggests ‘To have a thing painted and put on a canvas is not unlike buying it and putting it in your house. If you buy a painting you also buy the look of the thing it represents’ (Berger, 2008, p. 83). Furthermore the British pastoral countryside, through land management and its association of ownership, is often depicted as a safe rural idyll regardless of recent hardships such as floods and culling of diseased animals. (Wells, 2011, p. 164).

A photographer that explored the British landscape and the subsequent countryside social construct was Fay Godwin. Godwin was active from the mid 70’s to the early 1990’s with the most famous work being in the accessible printed form of books namely ‘Land’, 1985, and ‘Our Forbidden land’ printed in 1990. Both books, with their different agendas, offer the viewer an insight into the British landscape at the end of the 20th century and are the subject of this essay.

‘Land’ consists of 127 black and white images of Godwin’s work spread over 10 years within the landscape genre. The majority of ‘Land’ falls within a traditional romanticist view of the landscape, similar in tone to archetype British landscape painters Gainsborough, Constable and Turner. This aesthetic presents the countryside as the traditional pastoral scene and the rural idyll, but with a modernist focus on form and a photographic authority of authenticity and realism. Although the photographs are presented in this straightforward traditional aesthetic often associated with the unrealistic romanticist vision, Godwin strives for realism by avoiding picturesque imagery. On ‘the south bank show’ (1986) Godwin suggested a wariness of picturesque pictures commonly seen in commercial landscape photography such as that on postcards arguing that they were sentimental and idealistic, presenting the countryside in an unrealistic way (appendix A). Instead, Godwin was interested in the immediate scene explaining ‘I’m quite often frightened out in the landscape, and it’s often quite simply indifferent, and I’m interested all those different aspects’ (Godwin, 1986, pt. 1:27). These aspects are asserted in the organisation and order of the work with the book starting off in grandeur with impressionistic dark contrasting images of the Scottish highlands before turning to topography studies of ancient stones, farm buildings and rural pastoral land. However towards the end of the work there is an encroaching antagonism and disharmony with industry, power stations, and debris making appearances which Godwin uses to comment on environmental issues as if foreshadowing Godwin's follow up book.

‘Land’ is a broad study of British landscape featuring minimalism, juxtaposition, topography, and abstract studies amongst traditional landscape scenes. Subjects range from ancient monuments, farmland, village scenes, coastlines, moorlands, and mountains.

The majority of images are square 1:1 ratio, while others are slightly wider 4:5 and even wider 2:3. These ratios relate to the fact that the entire work is shot with medium format. Godwin was never brand loyal to one particular camera manufacturer, but had a soft spot for the Swedish Hasselblad namely the 500cm which took square 6x6 images. Other cameras used by Godwin include a Plaubel Makina which took 6x7 images (4:5 ratio) and a Linhof for wider 6x9 images (2:3 ratio). Lenses ranged from a very wide 21mm, to a standard wide 35mm to a standard normal 50mm (see Appendix B for emails from Peter Cattrell, Godwin’s printer).

Composition traits and techniques follow the simple rule of thirds with subjects off centre and land taking up three quarters of the frame. The use of symmetry, notably the square images, brings balance to scenes as seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 where the horizon line splits the sky and mountains from the moorland heath, further emphasized by the burning of the land creating two contrasting halves. Another trait is having the camera close to the ground, setting the viewer within the environment rather than looking down at it, this can be seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

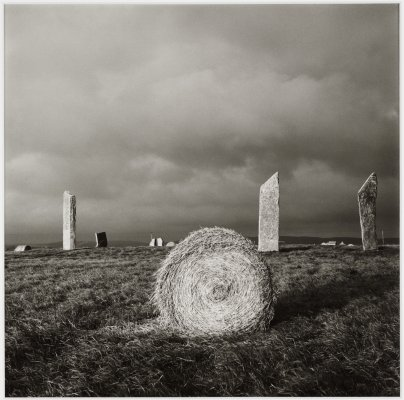

Juxtaposition as a pictorial visual device is used adjacent with topographic elements creating a contrast of time, history and physical attributes of artificial and natural elements. This can be seen in Figure 3 whereby Godwin uses a traditional pastoral emblem, the humble hay bale against the ancient stones. The cylindrical bale contrasts against the straight lines of the ancient stones, appearing modern and out of place yet here they both exist. This tension and questioning between both elements is enhanced with the looming dark skies which look to have been complemented with burning during printing.

A similar, more subtle, use of juxtaposition is seen in Figure 4. Godwin has used an ancient marker stone to playfully imitate the angle of the stone wall top left and also to connect with the wall at the top of the marker. The burning of the marker shadow and the adjacent rock ultimately creates a zigzag through the entire image hinting the notion of carved up and managed land.

Despite the images in Figure 3 and Figure 4 being of areas of agricultural land, more so in Figure 3 though Figure 4 could have livestock on the land, there are no people. This is a trait throughout the work. There are traces of people -paths, villages, churches, but never the rural people themselves. This emptiness and loneliness is a key theme to the work, it enables the work to be solely focused on the land.

Godwin has a tendency to fill the frame, getting the most out of the substantial negative size provided by medium format. By keeping cropping to a minimum at the printing stage (see Appendix B for emails from Peter Cattrell, Godwin’s printer), and by using all of the frame in terms of composition, composing completely in camera, the images have a consistency. This can be seen in Figure 5 whereby Godwin has chosen to embrace the environment and negative space surrounding the subject rather than cropping.

As discussed before, towards the end of ‘land’, there is an antagonism and conflict with society environmentally impacting the British landscape and threatening its safe pastoral countryside. This can be seen directly with pollution as in Figure 5. Here Godwin uses perspective, whether intentionally or not, by looking down at a rotting car half submerged in water. Godwin rarely used this visual trait opting for an immersive low down but level horizon perspective as seen in previous Figures. By looking down at the car and the lagoon, they appear weaker and fragile, perhaps to suggest about the fragility of the environment itself or to show the scene itself is something to look down upon.

Godwin also uses more subtle ways to introduce environmental issues into the work with visual metaphors such as Figure 6. A solitary broken bench looks out to sea, whilst an oil rig appears behind the rock formations as if to say the view is as broken as the bench. These environmental issues and related themes are explored further in Godwin’s follow up printed work.

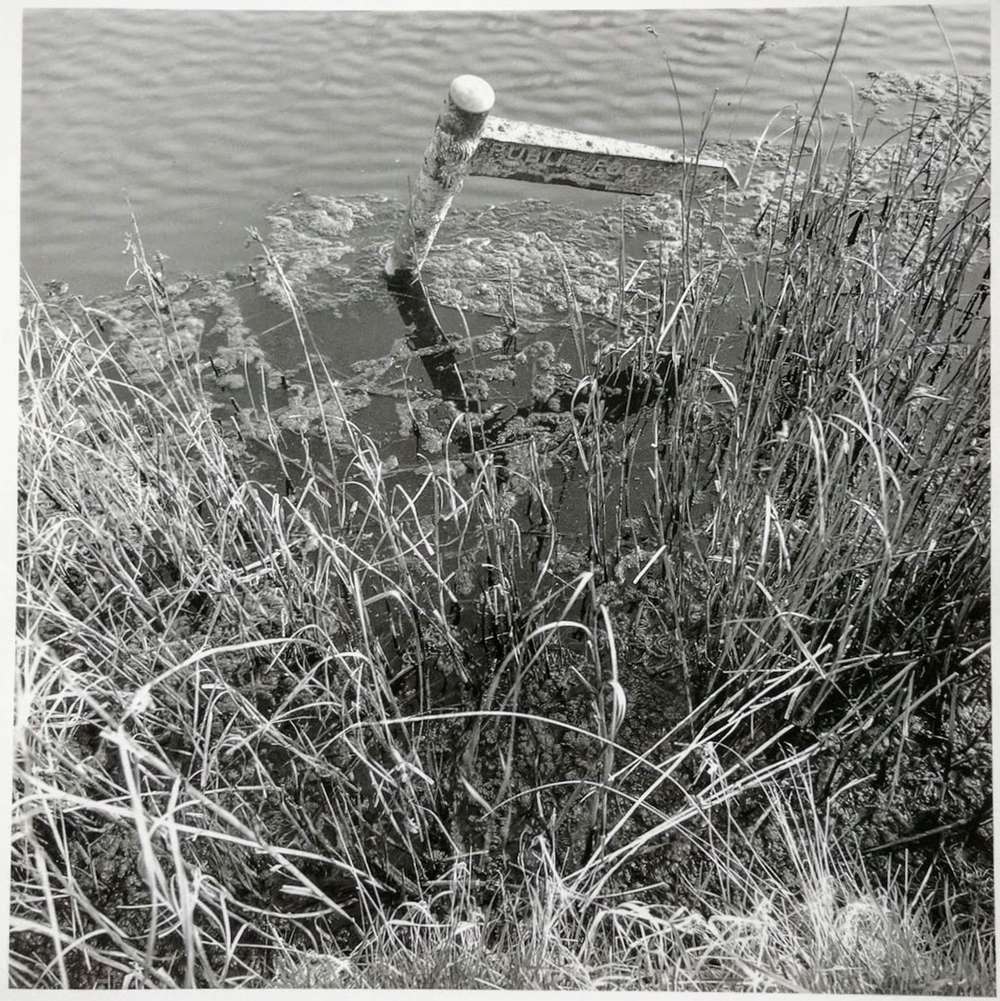

Following ‘Land’, ‘Our forbidden land’, printed in 1990, features 188 plates and a number of supporting images. The first image in the book as seen in Figure 7 epitomises the theme and voice of the work- a submerged public footpath sign amongst reeds. It echos the image of the rotting car in the previous Figure 5 with similar perspective. Additionally to the side, if the reader wasn’t clear about the message of this image, there are three contradictory quotes by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher on the subject of the environment.

Godwin’s political agenda is further voiced in the introduction written by herself, whereby revealing personal insights on copyright and restricted access to land, and discussing social environmental issues such as the use of pesticides and artificial fertilisers. This comes as Godwin, three years prior the publication of the work, was made president of the Ramblers Association, of which Godwin dedicates the book to. Being exposed to this political and active position, Godwin expresses concern for the conservative rural countryside, not just from contemporary society, but also from itself with ‘big business’ farmers using chemicals and exposing employees to poor working conditions.

In relation to photography, Godwin expresses concern about restrictions that present a legal minefield and potential headache for professional photographers.

‘It is extraordinary that Government agencies and others so often try to stop us photographing our heritage, our parks and gardens. They seem to think they can censor as well as try to copy-right the landscape and our heritage.’ (Godwin, 1990, p. 10)

This is particularly true for landscape photographers for example: the peak district, Britain's first national park, is 90% privately owned - only 17% of which is owned by the national trust and peak district national park authority with another 11% owned by water companies. So little of the land is actually free of copyright and is owned by many individual bodies rather than one collective. Understanding what is copyrighted and what is copyright free is commercially required and time consuming if the photographer has no local knowledge. (nationalgeographic.com, 2011). This introduction is supported by topographic images of signs displaying “dogs shot” and “keep out”. These range from farms, water companies and military installations.

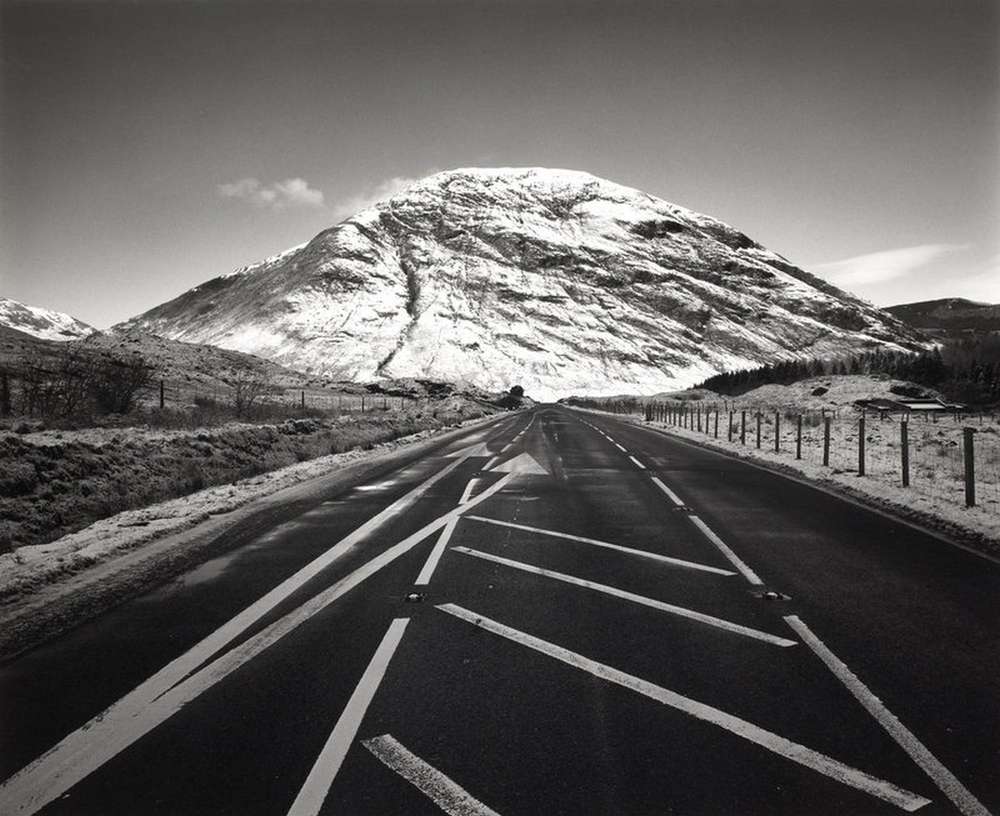

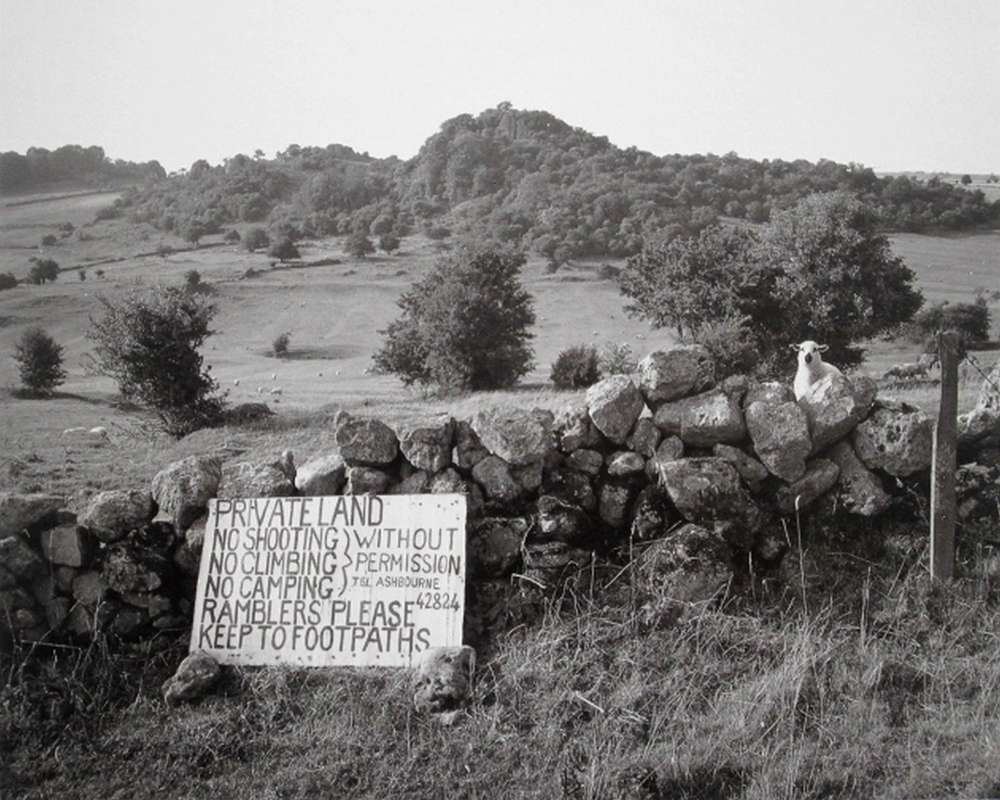

There are several different types of genre photography featured in this work. While there are landscapes in the traditional pictorial form like those featured in ‘Land’, there are also documentary and photojournalism styled images. The phrase ‘political landscape’ comes close to describing the work. Godwin, expressing political beliefs through photography, moves from the modernist focus on form to a postmodern focus of scrutiny. Figure 8 is the selected cover image and effectively summarizes the work itself. A dominant snow covered Glencoe mountain is juxtaposed against the black tarmac of the road cutting through the landscape and disappearing into the mountain. Two white road markings in the form of arrows enforce the leading lines from the road and roadside fencing, pointing to the mountain. These directional elements indicate a conflict between the more natural rural countryside and progressive modernisation with its tarmac arteries. Figure 9 is a photograph taken not far the peak district in Derbyshire. In the foreground, an excessive bold sign displaying various ‘Private land’ motifs is leaned against a low dry stone wall of which a sheep looks over and stares at Godwin. In the background is a vast pastoral scene complete with what looks like a tor and a small woodland. This image has humour with the watchful sheep, and irony that an excessive sign could be placed by such a low wall whilst showing the attitudes of the landowner to others. This image has a photojournalistic style while still retaining some of Godwin’s landscape traits such as the use of the rule of thirds.

The previous images fit the characteristics of Godwin’s medium format practice, particularly the 6x7 format, however there are other formats in this work such as the use of 35mm. Lighter, more portable, and favourable to the spontaneous style of photojournalism, Godwin uses 35mm film as and when needed with a leica rangefinder. (see Appendix B for emails from Peter Cattrell, Godwin’s printer).

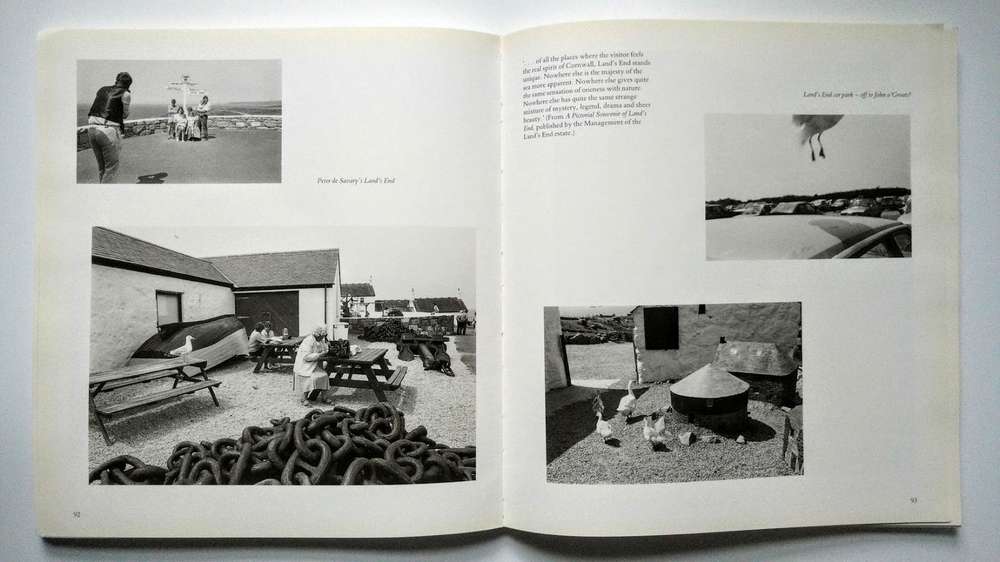

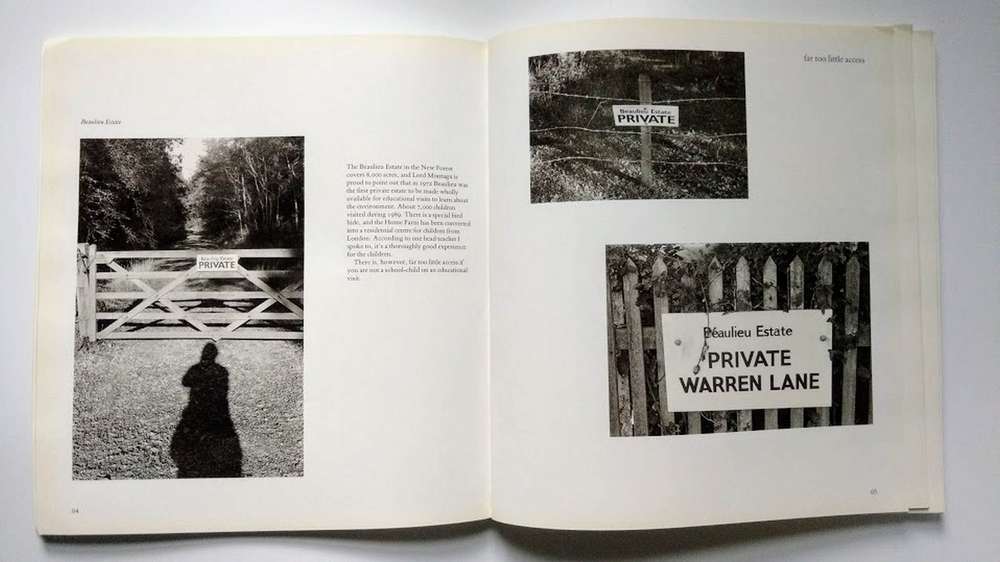

Figure 10 shows a spread within ‘our forbidden land’ from a series of images consisting of several pages exploring Cornwall. Here Godwin uses a photographic style akin to photojournalism through observation and non intervention, creating a narrative through sequential presentation of four images covering Lands end. Contrary to the loneliness of ‘Land’, Godwin captures people here to document Cornwalls tourism with an image of tourists photographing themselves by a Lands end signpost. Echoing Sontag’s statement: ‘Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, the program was carried out, that fun was had’ (Sontag, 2014, p. 9). By capturing the photographic act, Godwin shows the area is significant to tourists. The other images on the spread feature wildlife with a seagull sat amongst tourists at picnic tables, a miss framed in-flight seagull, and a bevy of swans in a model town showing Godwin’s humorous side. Figure 11 shows a spread under the title ‘Far too little access’ in which Godwin carries out, in a new topographic fashion, a topology study of estate signs in different forms. The left image is comparable to Lee Friedlander’s shadow images with Godwin’s use of shadow as a protagonist confronting the private sign being a subjective comment on restrictions to land (Sharpe, 2017, p. 268).

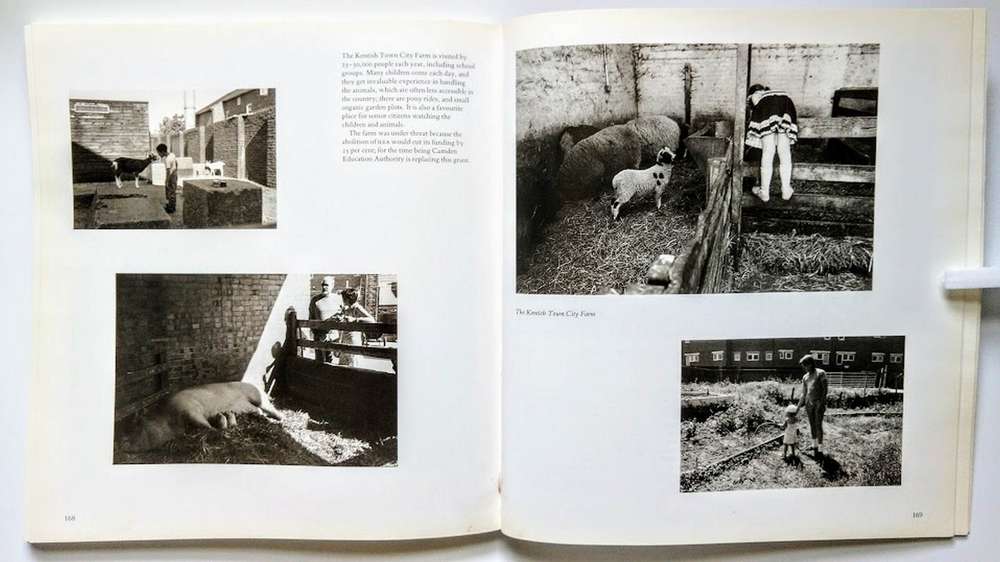

Through the use of the 35mm format, Godwin not only explores tourism, wildlife and topology but also society's connection to the countryside by covering rural food festivals, reclaimed urban land, farm oriented theme parks, and exploring public farms as seen in Figure 12. These images support the cultural construct of the countryside being a safe place whilst also showing the general public's exposure to rural environments that are fabricated and child safe. Godwin chooses to take a positive stance by photographing children interacting with animals. The spread in Figure 12 features 3 images of children. These 35mm film photojournalism images tend to be shot with a 35mm focal length lens, with which Godwin uses to place the subject within a surrounding environment creating an environmental portraiture style. These supplement Godwin’s people less medium format images which focus more on form.

There are exceptions in the work where Godwin favours medium format for documentary orientated images that are not pictorial in nature, but sombre in tone. This could be down to Godwin only having a particular camera at that moment in time, or felt the scene was worthy of a bigger negative. The image in Figure 13 is an example of this. Godwin uses a 6x7 medium format camera to capture farm rubbish dwelling near a footpath. These types of images are a continuation of ‘Rotting car, Cliffe Lagoon’ (Figure 5) and are usually printed on a full page.

Conclusions

On the surface, ‘Land’ is a book of accessible fine art images, which anyone with a passion for the countryside or pictorial landscapes can enjoy. Underlining this is a challenge to formal romantic depictions of the countryside. It can be seen as a modernist study of landscape with the use of black and white film putting emphasis on the shape and tone (Wells, 2015, p. 334). Additionally the aesthetic choice of monochrome is a form abstraction and reaction against picturesque commercial landscape images with vivid unrealistic colours. Godwin critiques postcards on the ‘the south bank show’ stating “I find most British postcards absolutely revolting” (Godwin, 1986, pt. 4:04). Nevertheless, monochrome is a key aesthetic and homogeneous feature throughout both works. The modernist focus of form attributes an objective and unsympathetic presentation whilst tonal values such burning of clouds and land help Godwin express the character of the space itself whether that be indifference, intimidation, or admiration of beauty (see Appendix A for Godwin’s thoughts on aspects of landscape). It is this subtle expression of character that challengers the safe rural construct and sets Godwin's work aside from exaggerated picturesque images which embellish rather than capture.

‘Our forbidden land’ turns the subtle expression of space through landscapes to a journalistic style critique of the British countryside. Through a postmodern scepticism, the work is critical of contemporary modern society but also rural inhabitants too. Godwin explores the countryside impartiality without bias for example, in the book, there are photographs of rubbish from farms and from urban visitors. This gave Godwin, a photographer that can masterfully capture a landscape to an extremely high standard, the incitement to photograph banal subjects like rubbish and debris. ‘Our forbidden land’ is broader than its predecessor with narrative driven photojournalism supplementing topography studies and political landscapes, making the work both ideology driven and artistic.

Fay Godwin as quoted on The South Bank Show 1986 produced by Hilary Chadwick. On aspects of the landscape:“In landscape there’s all sorts of things as far as I’m concerned. It is of course very beautiful in many ways but, that isn’t all that it is. I feel in many ways landscape can be quite threatening -I’m quite often frightened out in the landscape, and it’s often quite simply indifferent, and I’m interested all those different aspects.” (Godwin, 1986, pt. 1:27)

On the notion of picturesque:“I am kind of wary of picturesque pictures. I get sort of satiated with looking at postcards in local newsagents and at the sort of picture books that are on sale, many of which, don’t seem to bear much relation to my own experience of the place.” (Godwin, 1986, pt. 3:28)

"The problem for me about these picturesque pictures, which proliferate all over the place, they are a sort of blanket, they are almost like a very soft warm blanket of sentiment which covers everybody’s idea about the countryside. […] It idealises the countryside in a very unreal way” (Godwin, 1986, pt. 7:09)

Emails from Peter Cattrell who printed and worked with Fay Godwin. (Removed for public).

Berger, J. (2008). Ways of Seeing. Penguin UK.

Godwin, F. (1985). Land. London: Heinemann.

Godwin, F. (1986). The South Bank Show: Fay Godwin. ITV. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/4JE8I44Ak7o

Godwin, F. (1990). Our forbidden land. Jonathan Cape.

Godwin, F. (2005, May 31). No Man’s Land - Fay Godwin's last interview. Retrieved from ephotozine.com/article/ no-man-s-land---fay-godwin-s-last-interview-67 nationalgeographic.com. (2011, February 15).

Peak District National Park, England -- National Geographic. Retrieved October 9, 2017, from http://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/parks/peak-district-england/

Sharpe, W. C. (2017). Grasping Shadows: The Dark Side of Literature, Painting,

Photography, and Film. Oxford University Press.

Sontag, S. (2014). On Photography. Penguin UK.

Wells, L. (2011). Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. I.B.Tauris.

Wells, L. (2015). Photography: A Critical Introduction. Routledge.