Instead of a nature–culture dualism that has been eroded by historical events, a broad movement across the social sciences and social theory has advanced the claim that the world has always been comprised of entanglements between humans, creatures and agents of all kinds. This movement has been inspired by the philosophies of, among others, Bruno Latour, Donna Haraway and Gilles Deleuze and their antipathy to ontological hygiene. (Ginn, 2017, p. 5)

Ginn points to philosophers such as Bruno Latour, who’s 1991 work, Nous n'avons jamais été modernes, argues the dichotomy never existed.

… nature and culture are conceptual abstractions and so our present era – although it is an era of great loss – is not a loss of the wild brought about by the enclosure of nature within culture. Rather, the twenty-first century has witnessed a step-change in the intensity of planetary circulation and metabolism (Ginn, 2017, p. 5).

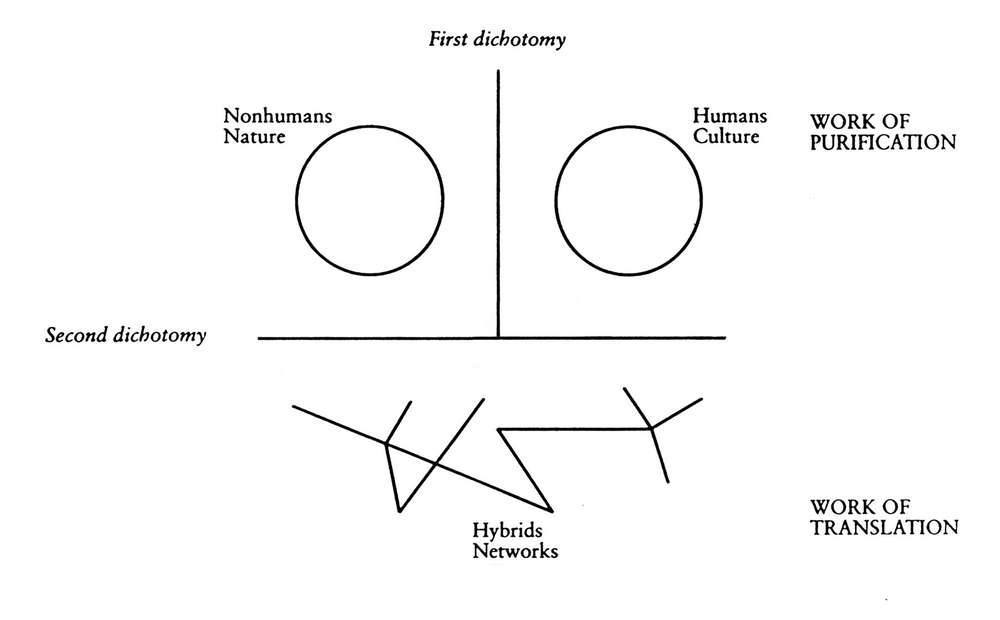

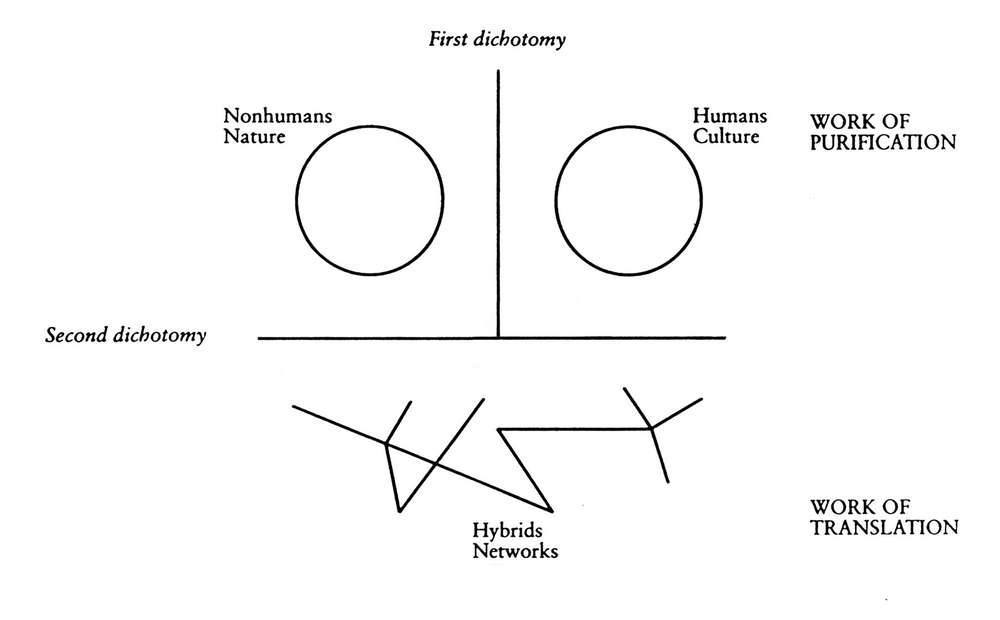

Ginn states that culture has not consumed nature (extinctions), but connected with nature through an increasing number of interconnections at a global level. This reminds me of fig.1.1 in Latours translated, We have never been modern? (Latour, 1993, p. 11) in which nonhuman nature and human culture are depicted along a second dichotomy separating the nature-culture dualism with that of a hybridised network of connections.

Gardening shrugs in the face of the nature–culture dualism. Gardening has never really been something done by humans to plants, but has always been a process of mutually beneficial interkingdom exchange. (Ginn, 2017, p. 6).

In relation to gardening, the interconnections between nature-culture are apparent and beneficial for both.

The Anthropocene seems to unite humanity. But it does so through ‘our’ unequally shared vulnerability to forces of capitalist world ecology and global environmental change. Instead of being united by negative unity – that of vulnerability and loss – might we not seek a more compassionate and affirmative acknowledgement of unity? Gardening, as the domestic wild, might allow us a way to imagine an earthly ethos fit for the Anthropocene. (Ginn, 2017, p. 142)

Ginn’s concluding message is that gardening may provide a force for good in the anthropocene landscape as a positive interconnection between nonhuman and human culture.

Ginn, F. (2017) Domestic Wild: Memory, Nature and Gardening in Suburbia. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Latour, B. (1993) We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.